Species Profile

In Pennsylvania, the black-crowned night-heron is listed as state endangered and protected under the Game and Wildlife Code. Nationally, they are not listed as an endangered or threatened species. All migratory birds are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

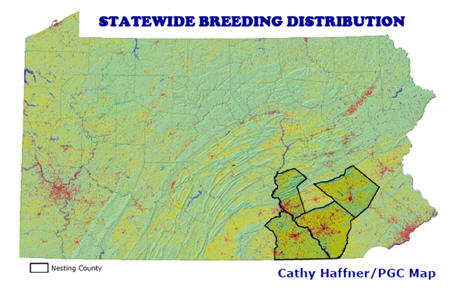

The black-crowned night-heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) was once considered a fairly common nesting heron in Pennsylvania. In fact, B. H. Warren (1888) claimed it was the most common nesting heron in the state second only to the green heron (Butorides virescens). Black-crowned night-herons have always been more common in the southeastern counties than in other parts of the state, mainly along the Susquehanna and Delaware River corridors, but the species is now difficult to find anywhere else in the state. The number and size of colonies have declined in recent years, especially in the northern and western counties (Luzerne and Crawford, for example) where the species no longer nests.

The Pennsylvania Game Commission and agency partners count active nests at known nest sites every year to monitor population trends. In recent decades, black-crowned night-herons were found nesting at locations in Dauphin, Lancaster, York, and Berks counties. Wade Island, Dauphin County, has been surveyed annually since 1985. This colony had the largest number of black-crowned night-heron nests for many years. It reached its peak in 1990 with 345 nesting pairs but has declined since then, primarily because of competition from double-crested cormorants that began nesting on the island in 1996. On Wade Island, the 5-year average night-heron count from 2005 to 2009 was 83 nests; from 2010 to 2014 it was 60 nests. During that time a smaller colony on hospital grounds in Lancaster County grew to be the largest, reaching 83 nests in 2012; since then it has declined as well. The geographic range of the back-crowned night-heron nesting population has changed dramatically from a much wider distribution to these few diminishing colonies on which we keep a close watch.

This medium-sized heron is very stocky and short-necked in appearance. The black-crowned night-heron is slightly larger than an American crow (1.6 - 2.2 pounds versus 1 – 1.4 pounds; Davis 1993), but less than half the size of the more familiar great blue heron (4.6 – 5.5 pounds; Butler 1992). The adults are distinctly marked with a black cap and upper back, contrasting with gray wings, rump and tail and white to light-gray breast. It is known by some as "the squawk" for its distinctive croaking call given at dusk as it flies to its evening feeding place. Juveniles have a streaky brown plumage with large white spots on the wing coverts. By contrast, the yellow-crowned night-heron is a smaller (1.3 – 1.8 pounds; Watts 1995), more delicate-looking heron with longer neck and legs.

Night-herons are very social; they nest in colonies and usually forage together. As their name suggests, night-herons are chiefly nocturnal and crepuscular in habit (that is, they are active at night or at dawn and dusk). They build simple stick nests in trees near where they hunt for food in shallow waters, opportunistically searching for a wide variety of prey items. If free of predators or human interference, they can maintain a colony for decades. They may not use a nest every year, but they may return to old nests after an extended absence. Night-herons are opportunistic predators, foraging for foods such as small fishes, crustaceans such as crayfish, insect larvae, leeches, mussels, mice, small birds, reptiles and amphibians, various plant materials, and carrion. Like most herons, black-crowned night-herons will take advantage of fish and crayfish hatcheries for food. Its high level on the food chain, colonial nesting, and wide distribution through-out its range make this species a good indicator of environmental quality and vulnerable to environmental contaminants.

Nesting can occur early in Pennsylvania (March-April) and continue through June or July, particularly if bad weather caused an early nest to fail. Black-crowned night-heron clutches throughout North America average 3-5 eggs (range 1-7) and are greenish in color (Davis 1993). Adults share the 24- to 26-day incubation period, sometimes fighting over trading incubation duties. They also share responsibilities of raising the chicks to fledging, six to seven weeks after hatching. Because the parents do not recognize their own chicks for a couple of months, juveniles can abandon the nest and continue to beg for food from any adult black-crowned night-heron in the colony. Juveniles will ultimately leave nesting areas with adults to travel to foraging areas. This dispersal following the breeding season allows for early morning or evening viewing opportunities along streams, lakes or ponds. By mid-September, birds travel to their southern wintering areas along the eastern and Gulf coasts of the United States and into Central America. Wintering birds have been observed at John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge (Philadelphia, PA) in small numbers (see McWilliams and Brauning 2000 for other locales).

The black-crowned night-heron is fairly widespread in distribution. Its nesting range reaches north into the Great Lakes, St. Lawrence valley and the coast of New England. Its habitat is quite varied, but always includes water. They can be found along coasts, along streams, in swamps, and in some human-altered locations such as canals and wet agricultural fields. Night-herons nest in trees, including native riparian species (sycamores, maples, ashes, birches) and exotic conifers.

In Pennsylvania, it is found primarily around rivers and creeks, often nesting on forested islands or along wooded streams. They can be fairly tolerant of human habitations and, if protected, will nest close to houses and in towns and cities. Proximity to humans may afford them some protection from predators. Dispersal following the breeding season can be to the north before they travel south to overwinter in warmer climates. So, many night-herons are observed in northern Pennsylvania after the nesting season is finished.

The decline in the number and size of Pennsylvania colonies is the main reason this species has been listed as endangered in the state. The remaining colonies are few and vulnerable to either human-caused or natural destruction. The state's largest colony on Wade Island in the Susquehanna River near Harrisburg is threatened by erosion and competition for nest sites with great egrets (Ardea alba) and a recent colonizer, the double-crested cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus). Population declines are not well-understood. Wetland losses in southern Pennsylvania may be an important factor in its decline. In the past, plumage hunters took a significant toll of nesting herons. Many waterbirds were hunted for their feathers because it was popular for women to adorn their hats with feathers and entire birds. Little is known about the impact of feral cats and dogs or nest predators such as raccoons and crows. Shooting birds at fish hatcheries, legal and illegal, is another possible factor in population declines. Little is known about the foraging range and preferences of the state's heron colonies so those vulnerabilities are difficult to assess.

Nesting colonies are protected through the Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program and the Environmental Review process. Colonies are monitored through the PGC's colonial waterbird program. The largest colonies are part of the Sheets Island Archipelago and Kiwanis Lake Important Bird Areas. More studies of the ecology and behavior of this species in Pennsylvania are needed to better understand its conservation needs.